More on Operation Freshman

Halifax B crash site Halifax B burial site Glider B crash site Execution site Memorial camp, SlettebøA Dangerous Mission

It now became of the utmost importance for the British to destroy this production, and an attack by airborne troops was chosen as the mode of attack. The task was assigned to the 1st Airborne Division of the Royal Engineers. The men who took part in the operation were all volunteers, even though they did not know what the assignment was or where it would take place. After much discussion it was decided to land the attack force by glider and, due to the importance of the task and the risky nature of the operation, it was decided that two gliders, each carrying 1 officer, 1 sergeant, 13 engineer soldiers and 2 pilots, i.e., a total force of 34 men, would be used so that if a problem occurred with one glider, the other would be able to complete the assignment. The soldiers and aircrew then engaged in a period of specialist training and practice for the mission.

The departure of the first Halifax tug aircraft and Horsa glider combination (Combination A) took place during the early evening of the 19th November 1942 from Skitten Airfield in the far northeast of Scotland. However, it is the second combination (Combination B) which left 20 minutes later, that we will focus on here, as both tug and glider crashed in the mountains nearby.

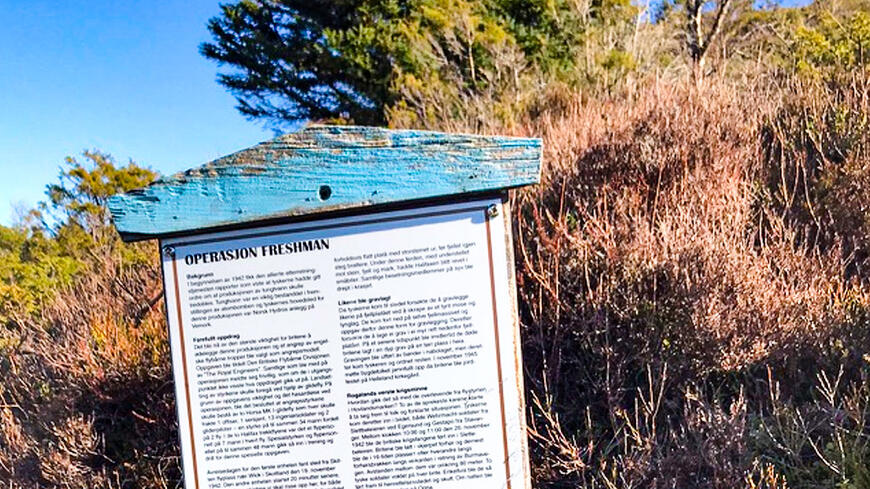

Horsa Glider crash on Benkjafjellet

Combination B lost altitude over the Helleland area, and after the tow-rope broke, the glider crash-landed northeast of Benkjafjellet on heathland belonging to Hovland farm. Three of the crew, including both glider pilots, were killed and three others seriously injured in the crash. The eleven remaining soldiers were more or less unharmed.

Two of the latter eventually managed to contact the local Lensmann (sheriff) and explained the situation to him. Given that urgent medical assistance was required and that it would have been impossible to keep an incident of this scale secret, the German Army in nearby Egersund was informed. Between 10:00 and 11:00 on November 20th 1942, the British soldiers were taken to the German army camp at Slettebø (near Egersund), where they were interrogated and photographed. At around 16:00 hours, they were positioned one after the other along a road in the camp (Burmaveien – The Burma Road). The distance between the men was about 80 meters and each was guarded by two German soldiers. They were then taken to a designated execution site and shot by a firing squad. At night, the bodies were removed from the camp and hidden in the sand dunes on the coast at Ogna.

The Germans' course of action should be seen in the light of the Hitler Order (Führerbefehl), which Hitler had sent to all senior German commanders on October 18th 1942. It stipulated that all those who took part in sabotage missions against German-occupied lands and who were taken prisoner should be immediately annihilated!

Halifax Tug aircraft crash on Hestafjellet

The Halifax tug continued at low altitude over the valley before crashing in the mountains on the other side of the valley from the glider crash site. The first eyewitnesses on the scene described a deep furrow in the ground made by the aircraft, the fuselage of which continued over Jonsoknudden and along a rock-strewn plateau before coming to a halt on Hestafjellet (where you are standing now). All seven crew members of the Halifax were killed instantly.

Burying the dead on Hestafjellet

A few days after the crash, the Germans tried to bury the bodies on the mountain plateau by scraping off a thin layer of moss and heather. However, they quickly encountered solid bedrock and abandoned this attempt. They then dug a grave in boggy ground just below the plateau and placed the bodies there. A short time afterwards a local farmer, Martin Sandstøl, discovered another body between some rocks and informed the Germans that there was still one of the Halifax aircrew who was not yet buried.

The actual burial was carried out very casually by the Germans and when spring came, corpses and body parts could be seen protruding from the bog. The local Norwegians made a request to the Germans that a proper grave be dug, a request which was at first refused. They then contacted the District Doctor, Münster Mohn, via the Lensmann (sheriff), who explained to the Germans that the bodies had to be cremated or a plague could break out. The locals offered to supply and transport sufficient wood to the site to carry this out, but before this was done, a counter-order came. The Germans requested that a proper grave be dug in a dry place with room for 7 coffins. This work was begun by local Norwegians, and then a German detachment completed the task.

To Helleland cemetery

After the war, orders came from the British authorities that the coffins should be exhumed and transported to Helleland churchyard, so that the dead could be buried in the cemetery there. Again, it was local Norwegians who took on the task. When opening the grave, they discovered that the Germans had nailed together four boxes without lids into which they had placed the bodies. It was hard work clearing the stones and gravel out of the boxes! Tillert and Sigvalt Helleren, each with a horse and sled, then transported the boxes down to the road where Ola Kvinen then drove them to the church. Erling Omdal and Sigurd Kvinen then placed the remains of the bodies in 7 coffins. The burial took place on November 21st 1945, and the church was packed with people. Jon Birkeland laid a wreath from the neighbouring farms, Norwegian soldiers carried the coffins and British soldiers stood guard of honour.

Original Norwegian text by Jostein Berglyd. English translation and minor modifications by Bruce A. Tocher.